Climate Control: Tropical Cooling Infrastructure & Sociality in Tengah’s “Forest Town”

- Yun Teng Seet

- Oct 24, 2024

- 19 min read

Updated: Nov 21, 2024

Abstract:

This essay examines the intersection of cooling, housing, and digital infrastructure in Tengah, Singapore’s first “eco-smart” housing estate. Using Tengah’s Central Cooling System (CCS) as a case study, it explores how techno-political narratives of comfort, modernity, and environmental sustainability inform urban living in tropical climates. Through the processes of 'cooling', 'leaking' and 'circulating', it analyses the enchantment surrounding “smart” environmental technologies as vehicles for progress and futurity. It then considers how the CCS, designed to offer a centralised, eco-friendly alternative to traditional air-conditioning, reflects broader ambitions of environmental mastery while simultaneously breaking down amid implementation issues and resident dissatisfaction. Through Telegram groups and online forums, residents share practical advice, frustrations, and support, fostering a digital sociality that parallels and critiques the physical infrastructure's limitations. Ultimately, Tengah and the CCS serve as a unique case study of the intersection of cooling, housing, and social infrastructure, and highlight a complex, evolving relationship between citizens and state-driven infrastructural initiatives.

Introduction

Opening the door, I walk into a thick wall of heat and humidity trapped within the dusty concrete walls of the new housing estate. I stride quickly over to the windows which face into the community square, struggling slightly on the catch as I push them open. A light breeze, along with harsh noises of construction works still underway, drift in. The site would remain under construction of years to come; this public housing estate, Plantation Grove, was the first of many that were launched in 2018 as part of Tengah, a new “eco-friendly, smart energy town” in western Singapore.

Future homeowners in a Telegram group chat [1], created in the years prior to the estate’s completion in 2024, discuss the heat, dust, and noise. One member quipped that they would tightly shut their windows and continuously run air-conditioning—electricity bills wouldn’t be a problem, with the new Central Cooling System (CCS). Touted as an energy-efficient cooling technology, Tengah would be the first experimental residential deployment of this “smart” system [2], made ever more urgent in Singapore’s tropical climate and high urban density. Six years since potential residents secured their flats [3], the promises of the CCS have started to falter. Shutting one’s windows and relying on internal climate control, it seems, is no longer a viable option.

In this essay, I explore how cooling, housing, and digital infrastructures uniquely intersect in Tengah. I will first analyse how the conjuring of imagined futures is key to harnessing the enchantment of “smart” environmental technologies in larger narratives of futurity and progress. Next, I explore how promises of tropical cooling are deeply intertwined with modernity and environmental mastery. I will then examine how these infrastructural “enchantments” fragment as they come up against contradictory realities of implementation, faltering alongside environmental “fixes” and rationalities. Ultimately, through studying the circulation of chilled air via the CCS and the circulation of sentiments on chat groups, I reflect on modes of living and sociality within this housing estate.

Figure 1. Open windows in an empty flat in Tengah Plantation Grove. Photo: Author, 20 March 2024.

Infrastructures of the Future

In the “HDB Hub” lobby, the Housing & Development Board (HDB)’s headquarters which doubles up as a sales centre, large displays advertise the state’s latest policies alongside intricately-rendered 3D models of the new Tengah estate. On this weekday afternoon, it bustles with people waiting for appointments. That was the reason why I was there—to collect the keys to a flat booked six years ago.

I glance at the display boards filled with pithy slogans, colourful diagrams, and computer-generated imagery. One reads “Going Smart Stretches Sustainability”, detailing a series of “smart” initiatives such as electricity sensors, lighting, irrigation, and virtual urban modelling. They form an infrastructural framework developed in 2014 spanning all public housing estates in which nearly 80% of the population live [4]. Such narratives, in which technological tools craft a future that is “comfortable and high-quality”, yet “efficient and sustainable” [5], are not new to a country in which “futurity itself becomes a mode of governing” (Roy 2016, 318). To understand the larger socio-technical framework of the CCS, I will first analyse how future-oriented promises of modernity and sustainability manifest in “eco-smart” infrastructures.

Figure 2. Artist’s impression of Tengah “Forest Town”, spanning 700 hectares and promising 42,000 new homes. HDB, 2016.

Figure 3. 3D model of Tengah Estate with informational boards at HDB Hub Atrium 1. @SingaporeHDB, 26 September 2016, Twitter/X.

Figure 4. Informational board “Constructing A Greener Future at Tengah” accompanied by a promotional video. Photo: Author, 20 March 2024.

The evocation of imagined futures to push action in the present is one that has been studied by scholars. In economic anthropology, Tsing (2000) has written about the power of “conjuring” in an “economy of appearances” that perform and dramatise potential to attract investment funds, while Bear (2014, 2020) argues that the divinatory deployment of “technologies of imagination” projects unseen ethical orders to navigate future uncertainty, ultimately towards value speculation and capital accumulation. Infrastructural technologies are also deeply entangled with political, ideological, and social imaginations of the future (Larkin 2013, 332). They not only perform technical functions, but are inscribed with affective desires and responses.

Harvey and Knox (2012), in following Bennett’s (2001) notion of “enchantment”, characterise infrastructural enchantments as bearing social promises which generate powerful affects—even as they come up against unstable forces of lived encounters and fail to materialise, they reinforce and amplify desires for generalised promises of a better future. These future-oriented promises ask participants to visualise what is yet to exist. Roy (2016) describes the emergence of a “politics of futurity” in Asia where narratives of crisis and uncertainty are reframed as ambition and aspiration towards development. Futurity itself thus becomes a means of asserting claims towards particular paradigms of growth and development.

In the case of Singapore, the conjuring of the city-state as a “Garden City” (Chua 2011) takes place alongside its digital ambition as a “Smart Nation” (Chong 2021). In the years following independence from British colonisation, Singapore faced fast-paced and condensed urbanisation alongside rapid economic growth (Shin et al. 2020). On one hand, the development of the “eco-city” as site of experimentation for new urban environments and technologies in response to climate change (Caprotti 2014) can also be observed as a form of “green spectacularisation” (Ren 2012). Such “solutions” reconfigure the city as green, clean, and inviting towards foreign investment (Schenider-Mayerson 2017, 170), and are predicated on “reordering nature and a revitalised modernist vision of infrastructural urbanism” (Whitington 2016, 415).

Additionally, Singapore’s intensive push since the early 2000s towards “smart city” imaginaries involved strategic policies to develop information infrastructure and “the extensive and systematic incorporation of digital network technologies across the urban landscape and population” (Ho 2017, 3102). Many have written about how “smart” urbanism goes beyond a material and technological phenomenon, encompassing “the techno-political ordering of society” (Sadowski and Pasquale 2015), producing self-regulating citizen-subjects through data collection and monitoring, and hindering political and environmental citizenship as it reinforces instrumental rationality (Ho 2017). The development of “eco-smart” infrastructure thus not only furthers these parallel imaginaries, but is also framed as a strategy of “survival” in relation to climate change and long-term environmental sustainability.

Heralded as “the future of living”, HDB’s “smart technologies” are first tested in new “smart towns” before they are deployed nation-wide. Considering the substantial role of the state in public housing, new housing towns are meticulously planned years in advance, and rely on the buy-in of potential homeowners to ensure their construction. Tengah, “the first HDB town…planned with smart technologies town-wide from the beginning” [6] and the CCS is thus a fascinating case-study to observe how various infrastructural enchantments intersect in future-oriented desires of “living well”, living green”, and “living connected”.

Figure 5. Screenshot from “Tengah”, Housing & Development Board, https://www.hdb.gov.sg/about-us/history/hdb-towns-your-home/tengah. Accessed 18 April 2024.

Cooling: “Living Well”

“Not cool enough” and “not the ‘usual cold’”. These were some complaints surfaced in Telegram groups by first users of the CCS. In the hot and humid conditions of Singapore, thermal comfort is a core concern. I first argue that the CCS’ infrastructural promises of cooling and climate control emerge from modernity and environmental rationality.

In his seminal book “The Air-Conditioned Nation” (2020[2000]), George noted that Singapore society could be analysed through its overreliance on air-conditioning, “a unique blend of comfort and central control”, and “where people have mastered their environment, but at the cost of individual autonomy, and at the risk of unsustainability” (20). Singapore’s first Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew considered the air-conditioner as the most influential invention of the 20th century, claiming that “historically, advanced civilisations have flourished in the cooler climates… and civilisation in the tropical zones need no longer lag behind” (19). The association of cool temperatures with comfort and control, along with mental concentration and productivity, is one that originates from colonialism in Southeast Asia.

Postcolonial scholars have shown how the construction of “tropicality” as a discourse connects climate with cultural otherness, race, and morality, associating cool conditions with hard-working individuals as opposed to hot environments with indolent people (Clayton and Bowd 2006). Atalas, in his well-known critique “The Myth of the Lazy Native” (1977), analysed how the colonial construction of Malay, Filipino, and Javanese natives as predisposed to indolence was, in fact, a natural physiological reaction of being in the tropics—heat necessitates rest, whilst temperate climates encourage work and action.

Thus, “comfort cooling” technologies have come to be considered central and inevitable to life in warm climates, and in Singapore, align with a modernist urban imaginary reproducing lingering colonial assumptions. Air-conditioning has allowed people to drastically reduce temperatures indoors, sealing off and mechanically controlling interior climates. One needs only to walk through the train stations, shopping malls, and office buildings in Singapore to feel the drastic changes in temperature, occasionally cooled to excessive levels and discomfort, prompting occupants to don extra layers for warmth. Air-conditioning thus materialises a particular relationship of environmental control, mastery, and externalisation, habituating bodies to particular thermal expectations and “enabling” the functioning of society. [7]

Figure 6. Promotional images and materials on MyTengah – an eco-smart energy town of the future. Note the use of phrases "Change the future", "Eco-town", and "Intelligent". https://www.mytengah.sg/centralised-cooling. Accessed 18 April 2024.

This is where Tengah’s cooling infrastructure enters. Conventional energy-intensive air-conditioning units use refrigerants to remove and channel heat externally, contributing to an “urban heat island” (Myrup 1969). In contrast, the CCS is presented as an eco-friendly alternative: pipes pump cooled water from centralised chillers on rooftops into individual flats. Smartphone applications permit control and “intelligent” monitoring of energy usage, while the network of chilled water and air promise up to 30% savings [8]. At the same time, air-conditioning is marketed as an essential utility, to encourage homeowners to opt-in to the service operated by state-owned national grid operator SP Group and private air-con manufacturer Daikin. Akin to “turning on a tap”, such “utility-grade cooling” is “just like electricity and water”—but at a “low[er] cost to the planet and your wallet” [9].

Contrary to other studies observing that infrastructures only “become visible on breakdown” (Star 1999, 380), the visibility of the CCS aligns with the future-oriented enchantments of urban domestic living. It promises a transformative shift from individualised, expensive, and unsustainable air-conditioning units to cheaper, ecologically-friendly systems which can more efficiently create the ideal and comfortable home, seen as essential to modern life. In furthering the state’s vision of “eco-smart towns” of the future, it therefore also functions “as technologies for materialising state presence” (Harvey and Knox 2012, 530) within the intimate, everyday spheres of one’s home.

Leaking: “Living Green”

In mid-2023, videos of flooded houses started to circulate on chat groups. Water leaking and condensation dripping from cooling units accompanied complaints of “disruptive” pipes which intruded into flats through the front door. I next examine how the infrastructural promises of the CCS start to break down.

Figure 7. Photographs initially circulated in online chat groups and published on The Straits Times (Liew 2024). Photos: Hamizan Jailani and Nur Afifah Hazali.

In Singapore, state-centric urban planning and public housing is crucial to the “reproduction of a workforce for global economic competition, the creation of a national identity, [and] the maintenance of political control” (Shatkin 2014, 129). On one hand, state control over public housing and a logic of pragmatism is essential in socialising Singaporeans into efficient and disciplined worker-consumer subjects (Tan 2012, 84). Conversely, more recently the contradictions of Singapore’s “illiberal democracy” (Chua 1995) have become increasingly urgent as it contends with widespread public dissatisfaction concerning rising costs of living and widening inequalities. Thus, eco-smart urban developments materialise a promise of state care for a population where the provision of basic public housing alone is insufficient—quality of life, environmental sustainability, and even technical innovation are increasingly seen as essential.

Telegram comments shed light on the expectations that Singaporeans have of the Tengah public housing project. Compounding dissatisfaction about construction delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic, photographs of the CCS trunking led members to comment that the size and intrusiveness failed to match early mock-ups, as “huge”, “ugly” “eyesore[s]” [10]. Next, as residents started to move into their flats, they reported incidents of CCS units leaking and flooding newly-renovated houses, and condensation from piping trickling down plaster walls and damaging interiors. Others complained about the units blowing warm air, and misrepresentations of the cost savings [11]. Residents’ dissatisfaction were exacerbated by SP Group’s deferment of blame, citing compressed timelines for workmanship, testing, and stabilisation of systems, and initially high cancellation fees for users wanting to terminate their contracts.

Figure 8. Photograph of pipe trunking and chilled water pipes entering an apartment above the front door. Due to thicker insulation, the trunking is larger than conventional units; the trunking pictured contains the main pipe supporting the whole flat, and thus is about 30cm wide. Initially circulated in Telegram chat groups and published on CNA (Koh 2023a, 2023b).

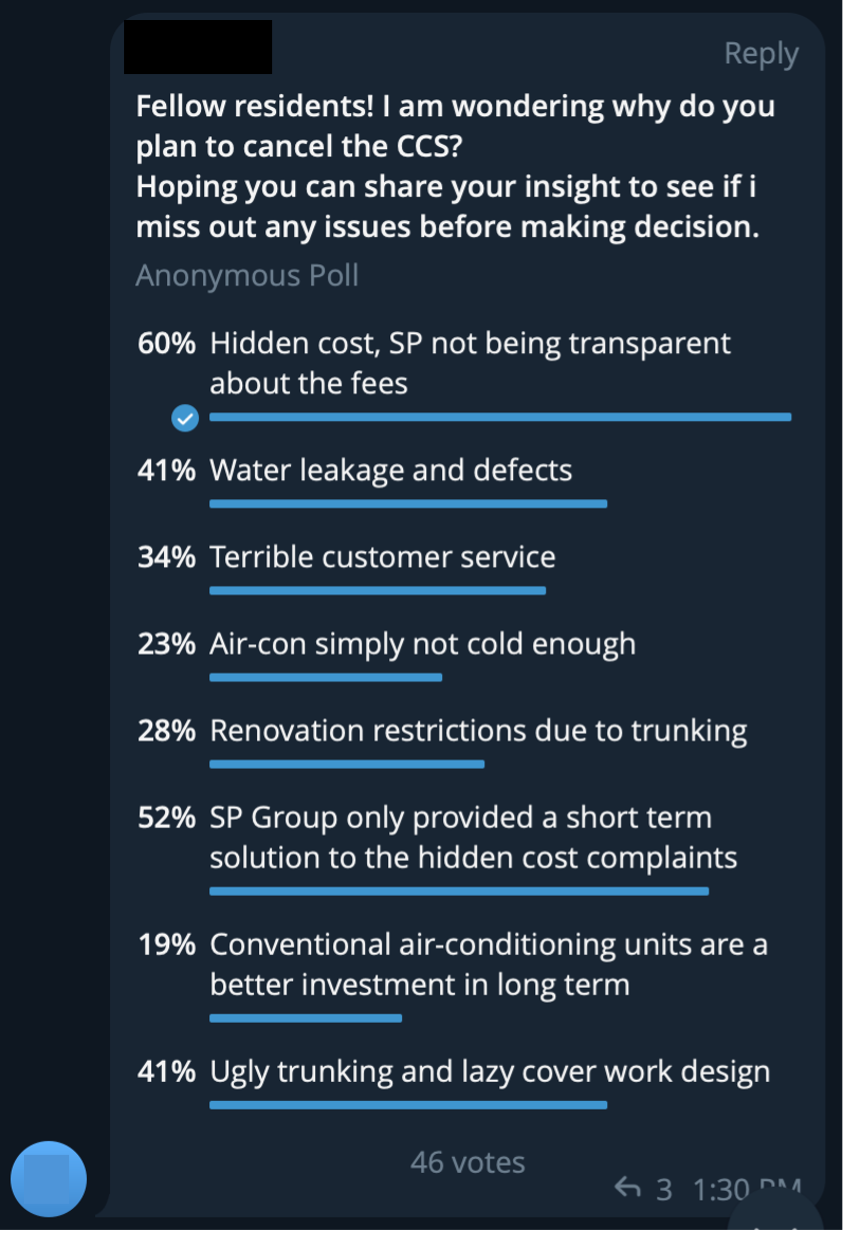

Figure 9. Screenshot of informal poll carried out on Telegram group, where a user sought feedback on reasons to cancel their CCS contract. Poll on “PLANTATION GROVE 2018(NOV)” Telegram group, posted 8 November 2023. Accessed 18 April 2024.

One frustrated forum user writes, “Look at it this way: It's an attempt by a govt official(s)/dept to fulfil KPI on GREEN INITIATIVES/CLIMATE CHANGE/ENERGY EFFICIENCY etc. It's not for your benefit.” [12] This comment sheds light on the public perception of the CCS as a “sustainability fix”. On one hand, such “green” initiatives primarily promise savings from reduced resource consumption: through an ability to track and render visible flows of electricity and chilled water, it “[prefigures] certain ways of seeing, knowing and governing the environment” (Ho 2017, 3108). Despite supposedly empowering the “smart” subject through promises of technological infrastructure, it instead narrowly produces and normalises shallow conceptions of environmental responsibility, guided by an ethos of cost efficiency and economic rationality (Wong 2012). Yet, in practice, the CCS failed to deliver on reduced bills, with users complaining about misrepresented rates and hidden costs. [13]

On the other hand, the “eco-smart” imaginary of Singapore emphasises selective implementation in urban governance in order to enhance an image of ecological modernisation. We can observe how, in the creation of Tengah “Forest Town”, an extensive secondary rainforest spanning 700ha was cleared. Despite HDB’s claim that forest and wildlife would be incorporated into the town’s planning, the Nature Society Singapore contended in a position paper (2018) that the area allocated (10%) would be insufficient and result in a drastic loss of flora and fauna. Despite recommendations for eco-links and habitat protection of threatened animal species [14], no changes have been made to existing development plans.

As such, we can observe the concept of a “sustainability fix” in the deliberate cultivation and manipulation of a “green” environment at the expense of natural biodiversity, and the use of “green” technologies which, rather than enabling “material changes in ecological footprint”, is often instead about “changes in political discourse” (While et al 2004, 554). It is clear that residents are increasingly disillusioned about the narratives around the CCS, with many chat group members expressing cynicism and distrust about its true environmental impact. Thus, the future-oriented enchantments of “eco-smart” infrastructures fragment in relation to both physical breakdowns as well as its failures in living up to the promises of cost efficiency and environmental sustainability.

Figure 10. Google Earth satellite images showing the deforestation of Tengah Forest between 2017 and 2024. Google Earth. https://earth.google.com/web/search/Tengah/. Accessed 1 November 2024.

Circulating: “Living Connected”

Walking along the corridors of Plantation Grove, a maze of pipes snakes overhead, in and out of apartments in this 12-storey block. Even for units without the CCS such as mine, pre-installed pipes connect my front door to my neighbour’s; they merge in the block’s basement as towering metal air ducts. Through circulation of air and circulation of sentiments voiced by residents, I lastly consider how cooling, housing, and social infrastructures come together in Tengah to generate modes of sociality and community.

Figure 11. Pipe trunking running between housing units and along corridors; meters displaying chilled water readings on pipes.

Figure 12. Chilled water pipes running throughout the building and air vents in the basement. Photos: Author, 23 March 2024.

Following the uprooting of kampongs (villages) and the displacement of rural dwellers to build modern public housing projects in the 1960s, the nostalgic romanticisation of the kampong spirit—communal solidarity and close-knit communities—pervades contemporary rhetoric (Kuah 2018). Regulations on ethnic quotas for allocation of flats and other state policies [15] also aim to construct neighbourhoods that are racially and socially-cohesive. I suggest that the CCS materialises some of the connections that flow within the housing block.

The CCS, as a centralised system new to domestic application, physically connects the entire building in a circulatory system of air and chilled water, in contrast to individual condensers. Pipe systems channel cooled water from rooftop chillers in and out of individual units—even if one does not switch on the CCS, they are billed for chilled water usage, cost-shared by the whole block, on top of individual electricity usage. Materially, this intertwines all residents in a housing block—despite living in separate flats, closed off from one’s neighbours, they have a shared reliance on the same infrastructure. This collective dependence also means that breakdowns necessitate the rallying of people to share resources.

One such channel is through Telegram groups, which serve as a key platform to resolve problems outside of official avenues seen to have “failed”. Such groups range from neighbourhood-specific to topic-specific groups such as “Tengah CCS Issue”, where CCS users discuss pros and cons of cancelling their contracts, ask for advice on maintenance and repair issues, and express opinions on questions of trust, responsibility, and blame. These groups, set up years before the physical buildings were completed, digitally connects one with future neighbours and creates a virtual sociality of a neighbourhood-to-be. On these groups, practical resources proliferate—from group buys for cheaper prices to key information dissemination—as well as messages of encouragement and commiseration over shared frustrations and anxieties, whether regarding the construction timeline delays or with failures of the CCS infrastructure. In some ways, these chats have become a parallel form of infrastructure, connecting residents in the circulation of sentiments, resources, and support in relation to physical ones, and create alternative neighbourly relations.

Figure 13. After a particularly heated exchange over the CCS in 2023, some members remind the group that everyone is entitled to their views, and that they have a long way to go as a community of neighbours. 8 November 2023, “PLANTATION GROVE NOV(2018)” Telegram group.

At the same time, just like the irony of half the residents opting out of the centralised system [16], individual tensions and disagreements co-exist with the collective. One can also abstain from participating in these digital groups, to passively lurk or not join them in the first place. Yet, just like in a physical housing block, the digital groups materialise a mutual entanglement that implicates one with their immediate neighbours—breakdowns of shared infrastructure (whether physical or social) inevitably have circulatory effects on everyone in the community.

Conclusion

In this essay, I have explored the unique intersection of cooling, housing, and social infrastructure in Tengah. By examining the ways in which “green” and “smart” infrastructures materialise future urban imaginaries intertwined with modernisation and economic growth, I first argued that the promises of cooling and comfort come with forms of techno-political control within the mundane contours of everyday life.

Next, I showed how infrastructural breakdowns reveal the perceived “failures” of the state in delivering on these promises, and undermine the trust and enchantment that residents had with the cost-effectiveness and environmental impacts of the CCS.

Lastly, through the metaphor of circulation, I suggested that the CCS physically materialises a shared nexus and collective involvement, and is paralleled in the digital infrastructure of online groups which perform an analogous social circulation of mutual entanglement. The processes of cooling, leaking, and circulating thus contribute to a unique sociality materialised by the “eco-smart” infrastructure of Tengah’s Central Cooling System.

This essay was written as part of"Digital Infrastructures", MA in Material and Visual Culture (Anthropology) at UCL.

Footnotes

[1] There are multiple neighbourhood-specific Telegram groups; entry into the group requires light verification of one’s ownership of a flat in that neighbourhood. Digital ethnography was carried out in the groups I was part of as a resident, “PLANTATION GROVE NOV(2018)”, as well as “Tengah CCS Issue” (non-neighbourhood-specific, no verification required).

[2] I use the term “smart” in relation to how it has been mobilised by the state and with an understanding of its discursive connotations. See later discussion on “smart cities”.

[3] The Build-to-Order scheme (BTO) is a unique and highly competitive real-estate development scheme by Singapore’s Housing and Development Board (HDB), which allocates flats to owners buying new public housing residences based on a ballot system. Tender for construction only takes place if at least 70% of the number of apartments are booked; homeowners thus have to wait for about 3-4 years for the flats to be built, which was delayed by an additional 2 years during the COVID-19 pandemic.

[4] In 2023, 3.18 million residents resided in HDB flats (76.6%). “Population Trends 2023”, September 2023, Department of Statistics, Ministry of Trade and Industry, Republic of Singapore.

[5] “Going Smart Stretches Sustainability”, The Smart HDB Town Framework. Display Board, HDB Hub Singapore. Accessed 20 March 2024.

[6] It also sits next to two major business and industrial districts, Jurong Innovation District and Jurong Lake District, planned to be Singapore’s second Central Business District. “Tengah”, Housing & Development Board, https://www.hdb.gov.sg/about-us/history/hdb-towns-your-home/tengah. Accessed 18 April 2024.

[7] Arguably, climate change and rising temperatures will come to necessitate cooling technologies, becoming not just an infrastructure of comfort but a “vital infrastructure” necessary for the support of biological life. Centralised cooling thus reflects Singapore’s approach to dealing with uncertain future climate risks in a “commitment to an artificial remaking of the environment through a rationality of control” (Whitington 2016, 420).

[8] According to initial marketing information on SP Group’s “MyTengah – an eco-smart energy town of the future”, https://www.mytengah.sg/centralised-cooling. However, this figure was later revised to be closer to 17%, and calculated based on a 20-year period as life-cycle cost savings (CNA 2023).

[9] Promotional videos “Episode 1 – How does Centralised Cooling work?” and” Episode 2 – Understanding Centralised Cooling's efficient system and technology”, MyTengah – an eco-smart energy town of the future, https://www.mytengah.sg/centralised-cooling. Accessed 18 April 2024.

[10] Comments made by J, Z, and A in 2023 on “PLANTATION GROVE 2018(NOV)”, Telegram group.

[11] As opposed to conventional AC systems where only electricity bills are incurred, with the CCS, residents would to pay for chilled water, whether they use it or not, on top of electricity bills.

[12] “Govt”: abbreviation of “government”, “dept”: abbreviation of “department”, “KPI”: abbreviation of “Key Performance Indicators”. Comment posted by stanlawj on 19 January 2024, on public forum post “Tengah Centralised cooling system (CCS) – Go or Not to Go for it?”. https://forums.hardwarezone.com.sg/threads/tengah-centralised-cooling-system-ccs-go-or-not-to-go-for-it.6986420/. Accessed 18 April 2024.

[13] The chilled water usage rate was first marketed by SP Group to be $0.09/kWrh, which increased to $0.2038/kWrh in October 2023. In response to complaints, SP adjusted the rate to $0.1220/kWrh (Koh & Tang 2023).

[14] These include the critically-endangered Sunda Pangolin, 4 globally threatened bird species, and 34 forest-affiliated resident bird species. This is further heightened by the fact that the Tengah Forest is isolated from neighboring forested regions by highways and buildings, creating a habitat ‘island’ which would be destroyed by the construction of Tengah Town (Nature Society Singapore 2018, 2020).

[15] Through HDB, the state implements housing policies which promote legislative agendas, including priority and funding for heteronormative nuclear family units to promote “core Asian values” such as “strong family ties and support, respect for one’s elders and communitarian values” (Goh 2001, 1592).

[16] An informal poll carried out in “PLANTATION GROVE 2018(NOV)” on 18 January 2024, indicated that half of the residents had opted out of the CCS. This does not include residents who had not signed up for it in the first place.

Bibliography

Bear, Laura. 2014. “Doubt, conflict, mediation: The anthropology of modern time: Doubt, conflict, mediation.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute, 20, 3–30.

Bear, Laura. 2020. “Speculation: A Political Economy of Technologies of Imagination.” Economy and Society 49 (1): 1–15.

Bennett, Jane. 2001. The Enchantment of Modern Life : Attachments, Crossings, and Ethics. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Caprotti, Federico. 2014. “Eco-urbanism and the eco-city, or, denying the right to the city?” Antipode 46(5): 1285-1303.

Chong, Alan. 2021. “Smart City, Small State: Singapore’s Ambitions and Contradictions in Digital Transnational Connectivity.” Journal of International Affairs 74, no. 1: 243–60.

Chua, Beng Huat. 1995. Communitarian Ideology and Democracy in Singapore. New York: Routledge.

Chua, Beng Huat. 2011. “Singapore as model: Planning innovations, knowledge experts.” In Worlding Cities: Asian Experiments and the Art of Being Global, eds. Ananya Roy and Aihwa Ong. Massachusetts: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 29-54.

Clayton, Daniel, and Gavin Bowd. 2006. “Geography, Tropicality and Postcolonialism: Anglophone and Francophone Readings of the Work of Pierre Gourou.” Espace Géographique 35 (3): 208.

George, Cherian. 2020[2000]. Air-Conditioned Nation Revisited: Essays on Singapore Politics. Singapore: Ethos Books. First published as Singapore: the Air-conditioned Nation : Essays on the politics of comfort and control. 2000. Singapore: Landmark Books.

Goh, Robbie B. H. 2001. “Ideologies of ‘Upgrading’ in Singapore Public Housing: Post-Modern Style, Globalisation and Class Construction in the Built Environment.” Urban Studies 38, no. 9: 1589–1604.

Harvey, Penny, & Hannah Knox. 2012. “The Enchantments of Infrastructure.” Mobilities 7(4), 521–536.

Ho, Ezra. 2016. “Smart Subjects for a Smart Nation? Governing (Smart)Mentalities in Singapore.” Urban Studies 54 (13): 3101–18.

Housing and Development Board. “Smart HDB Town: Smart HDB Town Framework”. N.d. https://www.hdb.gov.sg/about-us/our-role/smart-and-sustainable-living/smart-hdb-town-page. Accessed 18 April 2024.h

Hussein Alatas, Syed. 1977. The Myth of the Lazy Native: A Study of the Image of the Malays, Filipinos and Javanese from the 16th to the 20th Century and Its Function in the Ideology of Colonial Capitalism. London: Frank Cass & Co.

Koh, Wan Ting. 2023a. “‘It’s Very Ugly’: Tengah Flat Buyers Unhappy over Look of Centralised Cooling System.” CNA. 21 June 2023. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/tengah-bto-flats-aircon-trunking-centralised-cooling-system-3566821. Accessed 18 April 2024.

Koh, Wan Ting. 2023b. “‘Feels like a Fan’: Tengah Home Owners Raise More Issues with New Centralised Cooling System.” CNA. 13 October 2023. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/tengah-centralised-cooling-system-air-flow-not-cold-condensation-leaking-bto-flats-3834121. Accessed 18 April 2024.

Koh, Wan Ting and Louisa Tang. 2023. “SP Group to Cut Cooling System Usage Rate, Waives Fees until Year-End after Tengah Home Owners’ Complaints.” CNA. 7 November 2023. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/sp-group-cut-cooling-system-usage-rate-waives-fees-until-year-end-after-tengah-home-owners-complaints-3894456. Accessed 18 April 2024.

Koh, Wan Ting and Rebecca Metteo. 2024. “Leaks, Condensation Issues Persist for Some Tengah Home Owners Using Centralised Cooling System.” CNA. 20 February 2024. https://www.channelnewsasia.com/singapore/tengah-centralised-cooling-system-leaks-condensation-issues-persist-sp-group-daikin-hdb-4134051. Accessed 18 April 2024.

Kuah, Adrian. 2018. “Tropical Urbanisation and the Life of Public Housing in Singapore.” ETropic: Electronic Journal of Studies in the Tropics 17 (1).

Larkin, Brian. 2013. “The Politics and Poetics of Infrastructure.” Annual Review of Anthropology 42 (1): 327–43.

Liew, Isabelle. 2024. “Daikin Triples Workers Fixing Cooling System Defects after Some Tengah Residents Face Leaks.” The Straits Times. March 6, 2024. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/housing/daikin-triples-workers-addressing-cooling-system-defects-after-some-tengah-residents-face-leaks. Accessed 18 April 2024.

Myrup, Leonard O. 1969. “A Numerical Model of the Urban Heat Island.” Journal of Applied Meteorology 8 (6): 908–18.

Nature Society Singapore. 2018. “Nature Society Singapore (NSS)’s Position on HDB’s Tengah Forest Plan”. August 2018. https://www.nss.org.sg/nss_group.aspx?news_id=SsUTBU6iov4=&group_id=ohgTSSH5Yo0= Accessed 18 April 2024.

Nature Society Singapore. 2020. “Nature Society (Singapore) Conservation Committee: Nature Society’s Feedback on HDB’s Tengah Baseline Review”. June 2020. https://www.nss.org.sg/nss_group.aspx?news_id=Bf3QNqo6OUI=&group_id=ohgTSSH5Yo0=. Accessed 18 April 2024.

Ren, Xuefei. 2012. ““Green” as spectacle in China.” Journal of International Affairs 65(2): 19-30.

Roy, Anaya. 2016. “When is Asia?” The Professional Geographer 68(2): 313–321.

Sadowski, Jathan and Frank Pasquale. 2015. “The spectrum of control: A social theory of the smart city”. First Monday 20(7). http://first- monday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/5903/ 4660. Accessed 18 April 2024.

Schneider-Mayerson, Matthew. 2017. “Some islands will rise: Singapore in the Anthropocene.” Resilience: A Journal of the Environmental Humanities 4(2-3): 166-184.

Shatkin, Gavin. 2014. “Reinterpreting the meaning of the ‘Singapore Model’: State capitalism and urban planning.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 38(1): 116-137.

Shin, Hyun Bang, Yimin Zhao, and Sin Yee Koh. 2020. “Whither Progressive Urban Futures? Critical Reflections on the Politics of Temporality in Asia.” City 24, no. 1–2: 244–54.

Star, Susan Leigh. 1999. “The Ethnography of Infrastructure.” American Behavioral Scientist 43 (3): 377–91.

Tan, Kenneth Paul. 2012. “The ideology of pragmatism: Neo-liberal globalisation and political authoritarianism in Singapore.” Journal of Contemporary Asia 42(1): 67–92.

Tsing, Anna. 2000. “Inside the Economy of Appearances.” Public Culture 12 (1): 115–44.

While, Aidan, Andrew EG Jonas. and David Gibbs. 2004. “The environment and the entrepreneurial city: searching for the urban ‘sustainability fix’ in Manchester and Leeds.” International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 28(3): 549–569.

Whitington, Jerome. 2016. “”Modernist Infrastructure and the Vital Systems Security of Water: Singapore’s Pluripotent Climate Futures.” Public Culture 1 May 2016; 28 (2 (79)): 415–441.

Wong, Catherine ML. 2012. “The developmental state in ecological modernization and the politics of environmental framings: The case of Singapore and implications for East Asia.” Nature and Culture 7(1): 95–119.

![[Introduction] Conjuring Forms: Digital Translations, Material ‘Truths’, and Speculative Fictions in Post-Digital Contemporary Art Practices](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/ee39f3_47f2abd9db414c4697e4355a67689360~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_735,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/ee39f3_47f2abd9db414c4697e4355a67689360~mv2.jpg)

![[Bibliography & Artist Biographies] Conjuring Forms: Digital Translations, Material ‘Truths’, and Speculative Fictions in Post-Digital Contemporary Art Practices](https://static.wixstatic.com/media/ee39f3_0fadf58ef26d43bd9c31bcb2018b1a11~mv2.jpg/v1/fill/w_980,h_653,al_c,q_85,usm_0.66_1.00_0.01,enc_avif,quality_auto/ee39f3_0fadf58ef26d43bd9c31bcb2018b1a11~mv2.jpg)